When you are occupying a position which the enemy threatens to surround, collect all your force immediately and menace him with an offensive movement. By this maneuver, you will prevent him from detaching and annoying your flanks.

–Napoleon

Napoleon, meanwhile, made his headquarters in a palace in Warsaw, more than satisfied with his prospects. Thus far, the campaign had been an unqualified success, and the coming spring promised a crowning triumph against the Russians that would consolidate his stranglehold on English trade. The future had never looked brighter, and while passing through the town of Kiernoza on New Year’s Day, 1807, he encountered a girl dressed in peasant garb by the side of the road. Having waited for his carriage, she passed a bouquet of flowers through the window and greeted him with the words, “All Poland is overwhelmed to feel your step upon her soil.” The daughter of a nobleman who had been killed fighting for Polish sovereignty, her name was Marie Walewska and she idolized the French Emperor as the liberator of Europe and hoped-for savior of her country, which had been dismembered under the collective hegemony of Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

Later, upon meeting her at a ball in Warsaw, Napoleon invited her to join him in his palace quarters. What followed is the stuff of romantic novels, for Marie happened to be a married woman who had wed a rich Pole nearly fifty years her senior. Any fears she may have had about public censure for her conduct were quickly allayed, however, when members of the provisional Polish government officially encouraged her to accept the invitation–and all that it implied–for the sake of her country. Still, honor demanded that she resist the advances of even so illustrious a suitor as an emperor, and according to her memoirs it was only when Napoleon flew into a fit of amorous pique that she gave in to his advances. For Napoleon, the affair was hardly the first since his marriage to Josephine, yet his involvement with Marie Walewska was to be more than a mere dalliance; the relationship would indeed influence the cause of Polish independence and lead to the birth of a son, Alexandre.

The affair was abruptly interrupted, however, when renewed Russian activity at the front compelled Napoleon to take the field despite fierce winter conditions. The Russians, it seemed, were not through campaigning, and on 18 January they struck elements of Ney’s corps cavalry, eventually forcing both Ney and Bernadotte to withdraw southward. Napoleon first assumed that the attack was merely a reprisal for the marauding of Ney’s horsemen, but eventually recognized that the enemy was driving for the lower Vistula in an effort to reopen a corridor to Graudenz and Danzig. Despite the condition of his army, which had had precious little time to rest and refit, he quickly ordered his troops back into the field and undertook plans to cut the Russians off from Konigsberg.

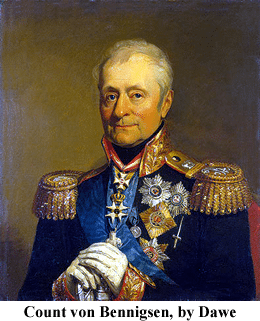

Begun on 30 January 1807, the French counterattack got off to a slow start due to poor road conditions, but the Grand Army soon lived up to its reputation for unmatched speed on the march, forcing the Russian commander, Count Levin von Bennigsen, to call a halt to his advance and draw up his army at Jonkowo. Here, quickly deciding to abandon his offensive, he faced about and for the next three days, with the French in hot pursuit, raced north to cover Konigsberg, outpacing the efforts of some 13,000 men under his subordinate, Lestocq. On the 7th, Bennigsen arrived at the settlement of Prussich-Eylau and began forming for battle on a series of hills immediately east of the town. On his heels was the French vanguard, which eventually won possession of the village and the shelter it offered against the bitter chill of the coming night.

The morning of 8 February 1807 dawned weakly through a dark overcast from which a foot of fresh snow had fallen in the night. Driven by a bitter wind, drifts up to three feet deep had accumulated in the Russian camps, where preparations for battle were already well advanced. Beginning at first light, Russian artillery batteries erupted along the entire front, marking the start of what was to be a very long day. Though substantially outnumbered, French gunners responded in kind and the smoke of battle soon contended with lowering skies to create a nightmarish scene.

With only 44,000 men on hand against some 72,000 Russians, Napoleon opted to await the arrival of Ney and Davout, at which point he planned to throw his main force against the Russian left and roll up the enemy line from south to north. About 9:30 Davout arrived in front of the village of Serpallen and immediately went into action, sending his leading division forward. Driving the Russians out of the village, the French repulsed an enemy counterattack and held on, fulfilling the first objective of the battle plan. Meanwhile, however, massed batteries along the Russian center were punishing the relatively weak French left, where Soult’s corps lay exposed to a withering bombardment. Aware of his vulnerability on the left and impatient to deliver a decisive blow, Napoleon decided to forego his original plan and sent Augereau’s two divisions forward against the Russian center while a third provided support on their right.

Advancing from the shelter of a concealing ridge, the French infantry no sooner came forward than they were subjected to murderous artillery fire. Adding to their peril, a heavy snow squall blew in on a stiff north wind, effectively blinding them while allowing enemy gunners, facing downwind, to zero in on the dark masses advancing across the plain. Dazed and disoriented as they waded through the deepening drifts, the French units lost contact and veered off course, actually coming under fire from their own guns as French artillery crews fired blindly into the oncoming blizzard. Pressing his advantage, Bennigsen unleashed his cavalry, which came driving down between the foundering French divisions and broke them apart. Augereau himself was wounded in the attack and his corps largely destroyed as a fighting force.

At this point, the snow abruptly stopped, and from a small hill near the center of the French line, Napoleon got a clear view of his shattered formations even as the Russian cavalry completed their rout. In response, he ordered Murat forward with four divisions of cavalry. Chasing off their Russian counterparts, the French horsemen pressed forward, smashing through the center of the Russian line to create a running melee in the enemy rear, whereupon the Russian foot soldiers closed ranks and faced about to cut off their retreat. Napoleon now sent the Guard cavalry to the rescue, and equal to the crisis, the veteran troopers opened another gap in the Russian infantry line, allowing their comrades to make good their escape and following them back across the center of the battlefield. Meanwhile, thousands of walking wounded–the remains of Augereau’s corps–were still struggling through the snow, to be battered about by alternating waves of horsemen. From his hilltop overlook, Napoleon now saw a column of Russian grenadiers emerge from a roiling sea of confusion directly in front of him. Nearby French infantry units quickly swung into action and the Emperor was soon out of danger, but the threat of his capture had been real, and despite his outward show of calm there was no concealing the fact that the battle was going badly for the French.

His attempted frontal assault on the Russian line having come to grief, he now fell back on his original plan to turn the enemy left. It remained for Davout to carry out the movement, but here again, the going was slow and difficult, the French gaining the village of Klein-Sausgarten only to lose it to a Russian counterattack. Eventually retaking the village, Davout’s troops poured a deadly enfilading fire into the Russian ranks and by five o’clock the Russian left, pushed back beyond the village of Kutschitten, was on the verge of collapse. Meanwhile, on the opposite end of the battlefield, a Russian cavalry attack went forward against the French left only to be broken up and driven off by Soult’s infantry arrayed in defensive squares.

Even as the French were scenting victory, however, Russian reinforcements under Lestocq arrived on the battlefield, passing behind Bennigsen’s line to envelop the French right at Kutschitten. Though worn down by days of hard marching, Lestocq’s 7,000 men pressed the exhausted French back upon Klein-Sausgarten to stabilize the Russian line. Now a final scene remained to be enacted in the day-long drama as Marshal Ney, following hard on the heels of Lestocq, arrived on the Russian right, formed for battle, and went forward in complete darkness, driving the enemy out of the village of Schloditten. Though his troops were too few and too weary to hold the place against counterattack, their eleventh-hour arrival may well have determined the outcome of the battle, for by threatening the main road to Konigsberg, Ney’s attack added fresh doubts to any thoughts Bennigsen may have entertained about continuing the contest the next day. In any case, the Russian commander opted to withdraw during the night, and thus the Battle of Eylau mercifully came to an end.

From a tactical standpoint, the contest was a draw, with both sides suffering horrific losses: 18,000 casualties for the French and as many as 23,000 for the Russians. Though the Russians abandoned the field, they were able to withdraw in good order and were in many ways better situated to pursue the contest than the French. Lestocq had come into line with his rear-guard still on the way, and with Konigsberg less than twenty-five miles off, Bennigsen could anticipate ample supplies and reinforcements. Napoleon, meanwhile, was far from his base, his troops exhausted from a week of fighting and marching under the most debilitating conditions, and any chance of mounting another offensive to drive the Russians from their own doorstep was doubtful. Though he made preparations to continue the fight the next day, upon discovering that the Russians had withdrawn to the north, Napoleon made no concerted effort at pursuit. After demonstrating in the direction of Konigsberg, the French withdrew to their original line (from Braunberg southeast to Ostrolenka), thoroughly fought-out. For all of its horrific losses, the battle had gained Napoleon nothing and would leave a lasting impression on him. Years later, from exile, he would claim that it was not the forces of his enemies that had defeated him, but the forces of nature represented by the sea that girded his empire in the west and the snow and ice that thwarted him in the east. At Eylau he came up against that eastern barrier for the first time and perhaps foresaw something of the fate that awaited him on the snowbound wasteland of the Russian steppe.