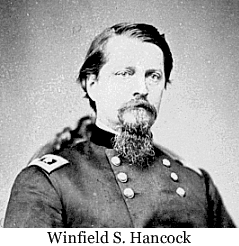

The directing person who would pick up the pieces after the death of Reynolds and the defeat at McPherson’s Ridge was Winfield Scott Hancock, who came into Meade’s headquarters about the same time as Buford’s message. Hancock was a thirty-nine-year-old Pennsylvanian, a West Pointer who looked and acted every inch a soldier. McClellan had pronounced him “superb” back on the Peninsula, and he was known throughout the army now as Hancock the Superb. Meade ordered him to turn his corps over to Gibbon and hurry to Gettysburg to take charge. (This decision would incidentally create an ugly little scene with Howard who actually ranked Hancock. Hancock, however, was a battler, and Howard had been driven from pillar to post in nearly every campaign.) Hancock climbed Cemetery Hill about four o’clock, just in time to witness the collapse of Doubleday and Howard north and west of the town. An officer with him described the scene: “Wreck, disaster, disorder, almost the panic that precedes disorganization; defeat and retreat were everywhere.” Two corps–20,000 men–had been wrecked. Nine thousand were dead, wounded, or captured. No one knew how many were still running, but a provost guard had snatched up more than a thousand skulkers on the Baltimore Pike alone. Hancock probably had no more than 7,000 effectives on hand when he reached the field. Hancock the Superb, however, was a calm and confident presence. He got weary troops back into line and digging on the north face of Cemetery Hill, then extended their works east to Culp’s Hill. To Culp’s Hill, which Howard had neglected to defend, he sent what remained of Wadsworth’s division from I Corps, and reinforced them with Slocum’s lead division as soon as it arrived. No less clearly than Longstreet across the way, Hancock could see the danger on the left. To Little Round Top he sent two of Slocum’s brigades under John Geary, and as the rest of Slocum and Sickles’ units came up late in the day and after dark, Hancock could extend his line down Cemetery Ridge between the Hill and Little Round Top. He had a naturally strong defensive position and the better part of four corps on hand to defend it. A dispatch went off to Meade saying as much. In three hours Hancock had forged a stout defensive line out of the pieces of disaster. In doing so, he had some assistance from Dick Ewell across the way, who failed to attack when the Federals were most vulnerable. Now he galloped off again to persuade Meade that this, not Pipe Creek, was the line to fight on. Meade, however, had already made up his mind to fight at Gettysburg, or rather, events had made up his mind for him. Gibbon would bring Hancock’s corps up, and Sykes and Sedgwick would be soon on the way. Meade himself reached the field by 3:00 a.m. on July 2, and rode through the gate of the Evergreen Cemetery. A sign nearby read: ALL PERSONS FOUND USING FIREARMS IN THESE GROUNDS WILL BE PROSECUTED WITH THE UTMOST RIGOR OF THE LAW. It was high summer and first light was only hours away.

Just as Meade reached the field, Lee was rising at his headquarters near Seminary Ridge just west of town. He had closed last night’s staff conference with this resolve: “Gentlemen, we will attack the enemy as early in the morning as practicable.” As practicable. Lee would discover today to his immense annoyance that his lieutenants did not share his idea of practicable. First, Old Bald Head’s opportunity to take the high ground–if practicable–had come and gone at dusk yesterday. He wasn’t at all certain he could do so today if Lee ordered it. A. P. Hill was visibly weak and ailing, not today the man who had come roaring down the road from Harper’s Ferry last September. Most unsettling of all to Lee was the continuing resistance of beefy, stubborn, strong-willed James Longstreet, whose objections today bordered on insubordination. If he thought an attack yesterday was unwise, he was more persuaded than ever today since the Federals across the way had been busy strengthening and extending their position all night. Lee repeated his stance: “The enemy is there, and if we do not whip him, he will whip us.” In the end, he gave peremptory orders: Longstreet would swing his corps to the right behind the screen of Seminary Ridge, form up behind the Emmitsburg Pike, attack the Federal left, and pry it loose from Little Round Top. His attack would be supported on the left by one of Hill’s divisions, Dick Anderson’s, which had not fought yesterday. As soon as he heard the guns of Longstreet’s attack, Ewell was to begin a serious demonstration against the Federal right on Culp’s and Cemetery Hill. If he saw an opportunity, he was to drive home an attack and take the position. Longstreet of course didn’t like the plan. To his other objections he added the fact that one of his divisions–George Pickett’s–was not up yet, and he never liked “to go into battle with one boot off.”

But battle it was to be, and the main Confederate effort was to be made by a man who did not believe it could succeed. It took time to get in position. The two divisions of Longstreet’s corps that would make his attack–John B. Hood’s and Lafayette McLaws’–had made a wearing night march to reach the Gettysburg area. Their roundabout route to the right was misled and the men had to countermarch a good stretch of it in the heat. By three o’clock, however, they were all in line in the woods behind the Emmitsburg Road, from right to left, Hood, McLaws, and Anderson from Hill’s corps, opposite Little Round Top and the southern stretch of Cemetery Ridge. To the north, Early’s division was opposite Cemetery Hill and Edward Johnson’s opposite Culp’s. (Pender, Rodes, and Heth’s divisions, so thoroughly bloodied yesterday, were in reserve today, and Pickett’s was still on the Chambersburg Pike.) Longstreet’s attack was supposed to go off in echelon, that is, in stages from right to left. As Longstreet prepared his attack, however, he discovered that the Yankees were not where they were supposed to be. The sector opposite Hood and McClaws was held by the Union III Corps under Dan Sickles. Sickles was a former Tammany Hall politician notorious as the murderer of his wife’s lover. (He was equally notorious in polite society for forgiving his wife and taking her back after attorney Edwin Stanton argued the first successful “temporary insanity” defense.) Sickles had not liked the look of the ground Meade had assigned to him. It seemed to him that slightly higher ground half-a-mile in front, out near the Emmitsburg Road, was more suitable. Accordingly, he pushed his two divisions forward, their left on a jumble of boulders known locally as Devil’s Den, their center in a peach orchard, and their right quite hanging in air. Not only was their right in the air, but Hancock’s corps, back on the ridge where it belonged, had its left in the air with a half-mile of open ground between it and Sickles’ right. Longstreet discovered one other development: the two blue brigades which had held Little Round Top last night were gone. Geary had been ordered that morning to return to Slocum’s division on the right.

Hood saw these developments as well as Longstreet and was sure the Round Tops were theirs for the taking. Guns there would enfilade the entire length of the Union line, and Hood wanted to swing his division right and seize that high ground immediately. Longstreet, however, whose counsel had been twice spurned, was not about to go to Lee a third time. It was Longstreet’s turn now to reject a subordinate’s best judgment, and he would in fact go his chief two refusals better. Three times he told Hood: “General Lee’s orders are to attack up the Emmitsburg Road”; to a fourth appeal he answered, “We must obey the orders of General Lee.” In the meantime, Hancock, too, had seen the trouble on his left. Not only was Sickles advanced a half-mile in front of the rest of the line, the front he chose was nearly two miles wide and that was nearly twice the front he left behind him. Sickles did not know it yet, but his 10,000 were now facing 15,000 Confederates in the woods across the pike. At 3:30 Confederate artillery opened up all along Longstreet’s front, and Meade rode up himself to investigate. What he saw would have infuriated a more even-tempered man than George Meade, but he had no time for rage now. There might be just enough time to get support up for Sickles, who, as Meade could see, was going to need it in a hurry. In doing so, Meade got a bit of good luck by way of the services of Uncle John Sedgwick. Sedgwick’s men had made a driving twenty-mile march from Manchester that day, and they were just now coming up the Baltimore Pike. Sykes’ three divisions had been in reserve just behind the Taneytown Road in the rear of Cemetery Ridge. As Sedgwick filed up behind them, Meade would be able to send Sykes on the double to the front.

At four o’clock the attack that Lee had intended for early morning went forward at last with a Rebel yell. The plan was to attack up the Emmitsburg Road in echelon by division, with the division attacks going forward in echelon by brigade, thus generating a series of successive blows south to north. The plan fell apart immediately. Hood’s right-most brigade was Evander Law’s, and it was supposed to strike the southern stretch of Cemetery Ridge. The rub, of course, was that the Yankees who held it were gone, now in a V-shaped salient near the road itself. An attack up the road, as Lee ordered and Longstreet insisted on, would put the Yankees in Devil’s Den on his flank. It seems a strange streak of stubbornness ran through the Rebel officer corps that day. Law simply ignored the order and drove his brigade due east in a frontal assault on Devil’s Den. This attack drew the three brigades on his left, one after the other, into Devil’s Den also, where all hell broke loose. One who survived it thought it “more like Indian fighting than anything I experienced in the whole war.” Hood did what he could to control the fight, which was not much, and he was soon unhorsed with an arm mangled by a shell fragment. “Every fellow was his own general,” a Texas soldier recalled, as the fight went fiercely back and forth on the rocky ground.

Evander Law, however, was managing to exert control on his front. His men were taking sharp fire from Yankee riflemen at the foot of Round Top on their right. He now sent two regiments under Colonel William Oates around to the south to drive them off. After a hard half-hour’s fight, they did so and continued up the steep wooded slope of Round Top–exactly what the wounded Hood had proposed and Old Peter refused an hour earlier. Oates was neither the first nor last man that day to see the tactical significance of this height. As soon as guns could be hauled to the summit and axemen clear a field of fire, he could blast Meade’s line to bits. Much to his dismay, therefore, Law ordered him down off his hill to take the lower hill just a half-mile north. This order would take him into the fight of his life. For about the same time Oates saw the opportunity this high ground represented, Gouverneur K. Warren, Meade’s chief engineer, saw the danger and sent to Meade for help at once. Sykes’ three divisions were already on their way to support Sickles’ embattled corps, and Meade now directed two brigades from Sykes’ first division, James Barnes’, to the left. One of these, Colonel Strong Vincent’s, was the first to arrive and Warren led them directly to the bare slopes of Little Round Top. They had just fifteen minutes to prepare to receive the attack Oates was now forming up for in the wooded valley between the heights. Oates would have five regiments to make his attack, three Alabama units and two from Texas. (The two Alabama regiments who had climbed Round Top with him had made a thirty-mile march to reach this field!) Defending the rocky slope were two blue brigades, eight regiments in all, Vincent’s with Stephen Weed’s just coming up, supported by two field pieces. “Don’t yield an inch” was Vincent’s last order. He fell, shot through the heart, in the first minutes of the fight.

For two hours blue and grey contested the possession of this most crucial piece of real estate. Confederates made five separate attacks and Federals five counterattacks. The “edge of the fight swayed back and forth like a wave,” one remembered. The struggle on the extreme Federal left was perhaps most desperate, but typical of the ferocity of the fighting all along this front. There the 20th Maine under scholar-turned-soldier Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain had reached the wooded slope with ten minutes to spare. His orders were to hold that position “at all hazards.” Across the way, the 15th Alabama came climbing up on the run and the fight was on. “The edge of the conflict swayed to and fro with wild whirlpools and eddies,” Chamberlain recalled. “All around, a strange, mingled roar.” Five times the farm boys from Alabama drove the bluecoats off, and five times the fishermen and lumberjacks from Maine fought their way back, each side firing in the other’s faces. With each attack, though, Oates’ men were slipping a little farther around to their right, threatening to flank Chamberlain and thus the Army of the Potomac. Chamberlain was forced to refuse his left, bending it back at right angles to his main line. Finally, with his regiment bloodied and his ammunition running out, Chamberlain decided on a last desperate measure: a bayonet charge. As the Alabama boys came on once more, the 20th charged down the slope, wheeling right, as one remembered, “like a great gate upon a post.” The charge knocked the Rebels off balance; then came the stroke that turned them back for good. Just before the Alabama storm broke on him, Chamberlain had sent Company B across the hollow to support his left, and that was the last he’d seen of them. Now they rose from behind a stone wall and delivered a murderous volley. Assailed front, flank, and rear, the 15th Alabama at last broke and ran. Chamberlain took 386 men into the fight; 130 were now dead or wounded. Oates’ casualties were at least as heavy. While the 20th Maine was making its fight here, Meade had been busy keeping reinforcements coming up. Although the rest of Hood’s brigades had by now driven the Yankees in a see-saw battle out of Devil’s Den, it looked as if the line on Little Round Top behind it would hold. Eight regiments had saved this stretch of the Union line, and one regiment, the 20th Maine, had saved them.

Whether Sickles’ salient to the right would hold, however, was altogether another question. Opposite the salient was McLaws’ division, ready to go forward as planned, brigade by brigade, right to left, aiming for Yankees in a wheat field just north of Devil’s Den and in a peach orchard just north of that. The fighting here would make these two pieces of country landscape forever the Wheat Field and the Peach Orchard. The men who would receive the attack were Sickles’ two divisions–David Birney’s and Andrew A. Humphreys’–both relatively small divisions of three brigades each. In support on their left were the other two brigades from Barnes’ division. (Two had gone earlier to the fight on Little Round Top.) At 5:30 Longstreet walked out as far as the Emmitsburg Road with the South Carolina brigade of J. B. Kershaw. He gave them a wave of his hat and a Rebel yell as they went forward to fall with a hard shock on Birney’s men at the edge of the Wheat Field. Shock was followed by shock, as McLaws sent in first Paul Semmes’ brigade, then W. T. Wofford’s behind it. It was a great deal of weight on a narrow front, and Birney’s line began to break up and stream to the rear. The pressure on Barnes’ front was likewise punishing. “It is too hot; my men cannot stand it!” he shouted, calling for a retreat. Then that whole length of line gave way. When Hancock had seen Sickles’ advance to the exposed salient, he had predicted that they’d come “tumbling back” soon enough, and so it was.

Although Semmes had been wounded in the assault, his comrades were eager to press the advantage they’d won. As they rushed forward in pursuit, however, they were themselves struck by a savage counterstroke. Hancock, alive to the danger on his left, sent his first division in, John Caldwell’s, and the battle in the Wheat Field blew up again. This time it was the Rebels’ turn to go tumbling back, only to form up once more and head back into the field. Now the fight went indecisively back and forth, regiments driving one moment and being driven the next. A Federal officer watching from the ridge thought, “What a hell is there down in that valley!” And so it was, for generals as well as enlisted men. Semmes was even then dying, and three of Caldwell’s four brigadiers were down, two killed. General McLaws, however, had one more brigade, William Barksdale’s Mississippians, to commit to the fight. Barksdale was a tall, white-maned West Pointer, who took frank pleasure in the shock of battle. He had in fact been begging McLaws for an hour for permission to pitch into the fight. Now he had it. Out of the woods and across the road his men came on the run, Barksdale in front, his face “radiant with joy,” a witness recalled. Humphreys’ men and a battery of guns in the Peach Orchard were overwhelmed in an irresistible rush. A Union colonel thought it “the grandest charge that was ever made by mortal man.” Four guns and a thousand prisoners were the immediate rewards of the assault, but Barksdale wanted more. He thought he could pierce the Union line on Cemetery Ridge just a half-mile away. Still in front, sword in hand, Barksdale led his men forward once more. Across the way, a Federal brigadier saw the white-maned Barksdale on the run and directed an entire company to draw on him. He was struck three times, through both legs and the chest, leading his last charge. The charge, however, went forward just as determined without him. On the ridge ready to receive it, however, was infantry supported by forty guns. Running on into a storm of canister and rifle fire, Barksdale’s men managed to reach the first line of guns, but another from the crest beyond drove them off. The survivors fell back on a little creek, Plum Run, just east of the Wheat Field. Half the brigade were still on the field, dead or wounded, and Barksdale himself would die behind the Federal line the next day.

The struggle on the Union left, however, was not over yet. Hood, then McLaws had struck, and both had gained some ground; now the Confederate attack shifted north once more, this time to Dick Anderson’s front. About 6:30, as Barksdale’s survivors were falling back on Plum Run, Anderson’s first brigade, Cadmus Wilcox’ Alabamans, went forward aiming for the section of Cemetery Ridge just north of the point where artillery had broken up Barksdale’s attack. The attack jumped off smartly, followed with equal precision by David Lang’s Florida brigade on Wilcox’ left and then Ambrose Wright’s Georgians on his left–and then stalled. Or rather, the two leftmost of Anderson’s brigades stalled. Next in line was Carnot Posey’s brigade, but he had already sent three of his four regiments forward as skirmishers and wasn’t quite sure what he should do with the fourth. In the end, the fourth regiment went as far as the Emmitsburg Road and was checked by artillery fire. On Posey’s left was William Mahone’s Virginia brigade. Mahone had a reputation as a formidable fighter, but today he understood that he was the reserve of Anderson’s division and refused to go forward–despite a message from Anderson himself. The problem was that no Confederate commander was really in effective control on this part of the field. Anderson’s division was in Hill’s corps, but the ailing Hill thought that, since Longstreet was in general command of the effort on the right, Old Peter would direct Anderson. Longstreet in turn supposed that Hill would guide him. Anderson, left to his own devices, let his brigadiers fight their own fight. All of which was unfortunate for the Confederate effort because the great opportunity of the day was right in front of Wilcox, Lang, and Wright on a thinly held sector of the Union II Corps line.

Hancock across the way was now responsible for the entire length of the Union line from Cemetery Hill to Little Round Top, commanding both his II Corps and Sickles’ III Corps. (A cannonball had torn Sickles’ right leg off earlier and taken him out of the war for good.) Sickles’ rash advance had wrecked that corps already, and now Hancock’s efforts to prevent a complete collapse on that front endangered his own. Sending Caldwell’s division to counterattack against McLaws had widened the gap on his left, and Wilcox’ brigade was driving hard for it. For Hancock, there was nothing to be done but call for help from Gibbon and Alexander Hay’s divisions on his right and hope Dorsey Pender opposite didn’t choose that moment to come crashing down there. Gibbon and Hay’s men were coming on the run, but so were the Alabamans now, driving the wreck of Humphreys’ division before them. It was going to be a near thing. As Hancock remembered it, “I saw that in some way five minutes must be gained or we were lost.” The first of Gibbon’s men to reach the crest happened to be the 1st Minnesota, commanded by Colonel William Colvill and just coming up in column of fours. In fact, it was only eight companies of the 1st Minnesota, three being detached elsewhere as skirmishers, leaving just 262 officers and men in all. “Colonel, do you see those colors?” Hancock asked their commander, gesturing toward the Alabama flag approaching the crest. Colvill did. “Then take them.” One who survived recalled: “Every man realized in an instant what that order meant–death and wounds to us all… to gain a few minutes’ time and save the position.” Down the slope they charged as the 1,600 muskets of the Alabama brigade charged up. The Alabamans had to pause to turn their murderous fire on the Minnesota men–a brief check. Ten minutes later 47 survivors under a captain returned to the ridge. On the slope, dead or wounded, were 215 of their comrades, Colvill among the dead. They never took those Alabama colors, but they gained Hancock his five minutes with five to spare.

Gibbon’s men made good use of the time, shaking out their battle lines and coming up to pour volleys first into Wilcox’ brigade and then Lang’s as it arrived on the left. Wilcox was also taking a destructive fire on his right, from the same massed guns that had torn up Barksdale. With no support forthcoming from Posey or Mahone, Wilcox and Lang had gone as far as they were going today and were forced to withdraw down the slope. Just as they turned to retreat, however, Wright’s Georgia brigade struck just 400 yards up the line hard enough to hold the crest itself briefly, but this stroke was too little, too late. Gibbon and Hay’s men were in strength here and on Wright’s flanks, and Meade was even then hurrying three divisions from Cemetery Hill to check the brief breakthrough. Without reinforcements, Wright, like Wilcox and Lang before him, was forced to withdraw, or rather, was forced to fight his way out against a Yankee outfit that had already gained his rear. The three Deep South brigades had threatened Hancock’s line, briefly pierced it, but in the end were beaten off, half of all those engaged now casualties.