You are going to undertake a conquest of which the effects on

world civilization and commerce will be incalculable.

–Napoleon, to his troops

Sailing from various ports along the Ligurian coast in the latter part of May 1798, the expedition rendezvoused at sea, eventually forming a flotilla of some 400 transports and 100 warships. On board was an army of 36,000 men, including the best elements of the Army of Italy, plus a large group of scientists and artists recruited for the enlightened purpose of civilizing the backward peoples of Egypt and uncovering the mysteries of a country little known to Europeans. Making its way down the Italian peninsula and into the open Mediterranean, the French armada took three weeks to reach its first objective, the island of Malta, where Napoleon made a landing in force and quickly set about establishing a new French protectorate, replacing the island’s existing defenders–the Order of Saint John–with a garrison force of some 3,500 French soldiers, and helping himself to the accumulated wealth of the order. After resupplying his ships from the island’s stores and replenishing his force with a contingent of Maltese troops, he was on his way again nine days later, keeping a wary eye out for the Royal Navy. On the night of 22 June, near the coast of Crete, the armada narrowly escaped detection by an English squadron under Admiral Horatio Nelson, the faster English ships passing them in the darkness. Arriving off Alexandria three days ahead of the French, Nelson would put about and head northwest only to miss his quarry once again.

Napoleon’s luck held with respect to the weather too, as conditions remained fair throughout the nearly two weeks that remained of the long voyage. Reaching the Egyptian coast on the last day of June, the French fleet concentrated six miles east of Alexandria off Marabout, where, amid stormy seas, Napoleon went ashore with about 4,000 men late the next day. By dawn, the assault force had reached the outskirts of Alexandria, and in stubborn fighting under a blazing sun, the invaders took possession of its strongholds. Once the new base was secured, the main body of the expedition came ashore, but when the ancient city’s port proved too shallow to serve as an anchorage, the fleet proceeded eastward to the shelter of Aboukir Bay.

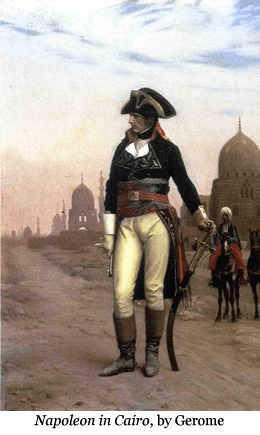

Casting his troops in the role of liberators come to free the Egyptian people from the rule of a warrior caste known as Mamelukes, Napoleon led the army southeast from Alexandria through fly-infested swamps and across the scorching desert toward Cairo, the French soldiers getting their first taste of a climate to which they were completely unaccustomed and an enemy eager to pick off any stragglers. A march of five days brought them to the banks of the western branch of the Nile at the village of El Ramanyeh, where they flung themselves into the muddy water to relieve their suffering. Waiting nearby were some 3,500 mounted Mamelukes, who combined superb horsemanship with reckless daring, and another 2,000 members of a professional warrior caste of Turkish origin known as the Janissaries. Employing a tactic designed to neutralize the enemy’s large cavalry advantage, Napoleon ordered his divisional commanders to deploy in battalion squares (hollow-centered battle formations as many as six ranks deep on a side). Though the Mamelukes attacked “with wonderful dexterity,” they could not penetrate the solid defensive walls of French infantry, and were soon driven off, leaving hundreds of their dead on the field. Meanwhile, a small French naval force made its way upriver to the site of the battle, where they were met by some 25 Egyptian gunboats and as many lesser vessels. Badly outgunned, the French squadron received much-needed help when their comrades on shore hustled a number of artillery pieces to the river bank and sank or drove off the enemy flotilla. Even so, with the loss of some 200 sailors, it was not a banner day for the French navy, whose fortunes would only grow worse with time.

Nor was the army in a position to do much celebrating with Cairo still a hundred miles away. Indeed, many of the French were to die of sunstroke, thirst, and exhaustion en route, while still others were driven to suicide by the harshness of the desert and the hostility of its inhabitants. Arriving at last outside Embabeh, immediately northwest of the capital, they discovered the enemy drawn up across their line of march in numbers nearly twice their own, a total of about 6,000 mounted Mamelukes supported by Egyptians whose numbers alone threatened to make up for the inferiority of their weaponry and tactics. Once again anticipating the greatest threat from the enemy’s cavalry, Napoleon ordered an advance in battalion squares with artillery positioned at the angles. Presenting solid defensive walls to the enemy attacks, the squares served as mobile fortifications against which the Mameluke horsemen could make no impression, their penchant for swarming around individual squares only exposing them to the concentrated fire of those nearby. Meanwhile, Napoleon led a reserve division around the enemy’s flank, cutting them off from their camp and shelling their rear, while two French divisions made a determined rush on Embabeh, sending its Egyptian defenders fleeing. Panicked by their first experience of heavy guns, many of the Arab fighters attempted to swim the Nile and were drowned. At a cost of some 300 French wounded, the Battle of the Pyramids–so named for its proximity to the ancient monuments–was a resounding French victory, adding fresh luster to Napoleon’s reputation for invincibility.

With the fall of Embabeh, the French swept forward as far as Gizeh, clearing the west bank of the Nile and opening the way to Cairo. Two days later they were in the Egyptian capital, the remnants of the Egyptian army having moved off to the south and east. No sooner had Napoleon established himself in the country’s interior, however, than alarming news arrived from the coast, where Admiral Nelson’s fleet had returned on 31 July to discover seventeen French ships of the line anchored in Aboukir Bay. Seizing upon the enemy’s vulnerable position, the English commander ordered an immediate engagement, sending five of his thirteen ships between the enemy vessels and shore to begin hammering them in a devastating crossfire. While the English suffered relatively little damage in the exchange, a total of thirteen French ships were either destroyed or captured, including the pride of the fleet, L’Orient, which blew up when fires reached her powder magazine. The rest of the French ships managed to escape to Malta, but the battle would effectively eliminate French sea power in the Mediterranean for the foreseeable future.

For the French army in Cairo, the implication of this stunning development was only too clear. Cut off from France, the expedition could expect no reinforcement or resupply, and thus what had begun as a campaign of conquest suddenly became a struggle for survival. Napoleon responded to the calamity by remaining outwardly undaunted and assuring his staff that they had the means to carry on the campaign unaided. Refusing to be controlled by events, he continued to pursue his original goals, establishing a French protectorate and implementing a variety of reforms and improvements throughout the country: creating a postal service, initiating the first extensive mapping of the region, and building a large hospital for the poor. French engineers even set about planning for a canal at the isthmus of Suez, and the chance discovery of an inscribed stone slab at Rosetta would enable French linguists to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs, unlocking the language of the pharaohs.

Nevertheless, the expedition remained stranded, and, under pressure from England, Turkey soon declared war on France with a plan to send one army on an overland route to Egypt while a second was assembled at Rhodes for a sea-borne invasion. Learning of these developments through increasingly rare communications with the outside world, Napoleon planned an advance of his own into Syria, thinking to cut off the Turkish approach. First, however, he sent a division up the Nile to deal with a still-active remnant of the Egyptian army under Murad Bey. Led by General Desaix, the detachment traveled by boat as far as Asyut before turning north to find the enemy at Sediman. Here, on 7 October, the French attacked in the same hollow-square formation that had succeeded at the pyramids, with much the same result. Fleeing southward, the routed Egyptians were eventually driven as far as Aswan by French cavalry.

Meanwhile, in lower Egypt a series of bloody revolts broke out, delaying Napoleon’s plans to head off the Turkish advance. Not until 6 February 1799 was he able to start east with some 13,000 men, leaving the rest of his army–approximately 16,000–to secure his base. Crossing the Sinai, the expedition laid siege to an enemy stronghold at El Arish, which fell on the 20th, yielding some 1,500 Turkish captives, who were released after swearing an oath not to take arms against the French again. This did not prevent the greater part of them from joining the Turkish force at Jaffa, however, and when the latter place fell two weeks later Napoleon was confronted with more than 2,000 captives whom he could neither feed nor trust to disperse. In response, he ordered all to be lined up and systematically shot. “A conqueror should know how to employ by turns severity, justice, and leniency in suppressing or preventing disturbances,” he later rationalized.

By 18 March the French had advanced northward along the coast as far as the massive fortress of St. Jean d’Acre. Surrounded on three sides by the sea and on all sides by massive walls of stone, Acre was further defended by an English naval squadron under Sir Sidney Smith, who had the good fortune to capture a small fleet of French transports en route from Jaffa loaded with heavy siege guns. These he quickly employed in the city’s defense, along with the firepower of two ships of the line. Nevertheless, Napoleon was determined to lay siege to the fortress just as Alexander the Great had done in the fourth century B.C. Where Alexander had succeeded, however, his French successor would fail. Transporting the balance of his heavy guns overland from Jaffa, he managed to batter down part of the massive walls but was stymied in his efforts to take the city by storm. On 9 April, with a Turkish army of some 20,000 men moving toward his rear, he sent Kleber’s division inland in an effort to outflank the enemy upon his approach. Instead, the Turks managed to surround Kleber on Mount Tabor, immediately east of Nazareth, forcing Napoleon to abandon his siegeworks and come to the rescue. Catching the Turks as they were about to fall upon Kleber’s isolated force, he put them to rout and the French moved quickly to resupply themselves from the spoils.

With the defeat of the Turkish land army, Napoleon fulfilled the strategic objective of the campaign and was free to return to Egypt to prepare for the expected sea-borne invasion from Rhodes. Even so, he remained in front of Acre, determined to prevail if only for the sake of his own legend. On 7 May, with a fleet of Turkish reinforcements approaching the besieged city, French forces made a last, furious assault on the walls, breaking into the fortress only to be driven out by a detachment of English sailors. Thwarted in his attempt to replicate the feat of Alexander the Great, Napoleon flew into a rage, calling the assault troops “sissies,” but with the arrival of the Turkish reinforcements he recognized the futility of any further attempts, and on 20 May he reluctantly abandoned the effort.

By this time his failure to duplicate the triumph of Alexander was the least of his concerns, for his exhausted troops had begun to fall victim to an outbreak of bubonic plague, creating justifiable panic throughout the army. In an effort to inspire confidence, Napoleon made a personal visit to the plague hospitals, exposing himself to the disease for the equivalent of a modern-day photo-op (the occasion would be duly committed to canvas if only for public relations purposes). This gesture could hardly be expected to restore the sick to health, but he did what he could for them, ensuring that they received the best of the remaining rations and assigning all of the expedition’s horses, mules, and camels to carry those sick men well enough to continue the journey back to Egypt. This left the rest of the army, including the commander, to make the trip afoot in punishing heat. By the time they completed their journey, fully a third of the original force had become casualties.

On 14 June the ragged survivors arrived back in Cairo, where a victory parade was held to celebrate their success. Under the circumstances, it was a case of whistling in the dark, for while the threat of a Turkish overland incursion had been dispelled, the army’s losses had been irreplaceable, and its prospects as an occupying force were growing darker by the day. Without reinforcements or the possibility of returning to their homeland, the French faced a bleak future amid an increasingly hostile population, for local uprisings persisted, and all along their supply routes the French were subjected to raids and guerilla attacks. Then, on 11 July, came news from the coast that the Turkish sea-borne expedition from Rhodes had arrived in a fleet of 100 ships. Landing at Aboukir, 15 miles east of Alexandria, the enemy had occupied a fort at the top of Aboukir Bay and was preparing for battle.

Napoleon wasted no time in obliging them. Recalling Desaix’s division to Cairo from Upper Egypt, he held General Reynier’s force in reserve to defend against an incursion from the east, concentrating the rest of the army on Alexandria. By the 24th he had close to 8,000 men on hand with which to confront as many as 18,000 Turks. Their commander, white-bearded Mustapha Pasha, had stationed his frontline troops on three hills along the approaches to an extensive peninsula dominated by Fort Aboukir. In front of them, a solid Turkish battle line stretched across the neck of the peninsula. Early on the 25th, Napoleon sent two infantry divisions forward against the outlying hills, with a cavalry force between them. While the infantrymen assailed the enemy positions in front, the cavalry commander, Murat, divided his force into two wings and sent them wheeling around the enemy’s flanks. Swift and brutal, the French horsemen overran the isolated positions, driving many of the defenders into the sea. When a Turkish sortie was sent out to support their fleeing comrades, it was met by a fresh division of French infantry and Murat’s ubiquitous horsemen, who once again rode around and behind them. Assailed on all sides, the would-be rescuers soon joined their countrymen in headlong flight for the relative safety of the sea.

Their front line defenses thus shattered, the remaining Turks awaited attack behind a secondary line near the tip of the peninsula. Here an initial French infantry assault was thrown back with considerable loss and the Turks rushed forward to take the heads of the fallen. No sooner had they set about their grisly business, however, than they were caught and overrun by a timely counterattack. Meanwhile, General Murat exploited a gap along the bay shore to drive once again into the enemy rear. Amid a force of janissaries, Mustapha Pasha put up fierce resistance, but in the end, he too was routed. Apart from some 3,000 survivors who held out in Fort Aboukir for another week, the Turkish army had been utterly destroyed, with 2,000 dead on the field and as many as 10,000 drowned while attempting to swim to safety. At a cost of about 150 French dead, Napoleon had redeemed the failure at Acre and provided convincing evidence of French military dominance.

And yet the French remained a long way from home and short on hopes of returning. During negotiations over the Turkish wounded, Sir Sidney Smith had seen to it that a packet of newspapers was sent ashore, in which Napoleon learned of disastrous developments on the continent. In the year since the expedition had departed, two French armies had suffered major defeats and a new coalition including England, Austria, Russia, Naples, and Turkey had declared war on France, undertaking a three-pronged invasion of newly-won French territories. In addition, a paper dated 10 June 1799 reported that an Austro-Russian army had invaded northern Italy, reclaiming all of the hard-won territory Napoleon had conquered in his previous campaign. Furthermore, it seemed France was on the verge of economic collapse, and in response, Napoleon made a fateful and revealing decision. Under the circumstances, the country surely needed her most successful general at home. For all he knew, the Directory had already sent for him, (which indeed proved to be the case). Whatever the risks, whatever the world might say, he must make every effort to return to the capital as soon as possible. Thus, placing General Kléber in charge in Egypt, he secretly arranged for four small ships to carry him and a select group of officers back to France, and on 22 August 1799, the small flotilla put to sea. The rest of his army and the artists and scientists he had invited on his great adventure would be left to their fates.