To the drum-taps prompt,

The young men falling in and arming…

Squads gather everywhere by common consent, and arm.

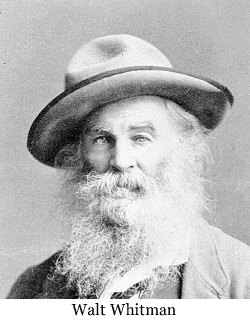

–from Drum-Taps, by Walt Whitman

North and South had been talking about just such a trial for a generation. Neither side, however, was at all prepared to prosecute the war that had been threatened so long. Americans had nurtured from their beginning a deep distrust of a standing army, believing it a danger to republican government. In 1860 a nation whose population was nearing 30 million fielded a regular army of slightly more than 16,000 officers and men. Most of these were scattered across three million square miles of the trans-Mississippi West. It was a force hardly adequate to keep in check the Western tribes, secure the emigrant trails, and garrison a hundred-odd forts and posts. As historian James McPherson points out, the regular army “had nothing resembling a general staff, no strategic plans, no program for mobilization. Only two officers had ever commanded as much as a brigade in combat, and they were both over 70.” The United States Navy was hardly better prepared; although it had 42 ships in service, most of these were on the high seas. Less than a dozen warships were ready to cruise the vast reaches of America’s own coast. In fact, so unprepared for war was the United States that in the first days of the conflict the capital itself was virtually isolated and undefended. Lincoln’s call to arms after the fall of Sumter had driven the four states of the upper South–Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia–to join their sisters in the lower South. With slave-holding and secession-minded Maryland north of the Potomac and Virginia south of it, Washington endured 10 anxious April days before the first regiments from Massachusetts and New York relieved the city.

In Washington then the government was committed to the suppression of a rebellion; in Montgomery, Alabama (very briefly the Confederate capital), the government was determined to secure the independence it had proclaimed. Neither side had the means at hand to achieve its end. After the fall of Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 ninety-day volunteers and a month later for 42,000 three-year men. These were to be raised by the states’ militia systems and then sworn into federal service. Under the existing militia system, however, the task would prove enormous. Except for the brief, fitful outbursts of the 1812 War and the Mexican War, the country had enjoyed a half-century of peace, which had bred a generally incompetent complacency, with annual militia musters having much more the air of a country fair than a military exercise. In the outpouring of pent-up energies after Sumter, Lincoln could find many willing hands to do the government’s work, far more than the 75,000 he initially asked for. The rub was that the militia–officers and men alike–brought a great deal of energy but precious little useful training or experience. Thus the larger problem was what to do with this mass of men once they came into the federal service. The task of organizing, training, arming, and equipping a force this large was in the spring of ’61 utterly beyond the government’s immediate power to accomplish efficiently or effectively.

In the South Jefferson Davis was in the same headlong rush to raise an army and was in fact a step or two ahead of the Northern mobilization. By many lights (certainly by his own), Davis looked the ideal choice to engineer such an effort. A West Pointer, he had seen service in the Black Hawk War and the Mexican War and had been a capable Secretary of War to President Franklin Pierce. Davis had called on the states for 100,000 militiamen more than a month before Lincoln’s call, and it may be that the Southern militia system, incited by John Brown’s raid, was in a somewhat higher state of readiness than its Northern counterpart. The South was, however, even less prepared to feed, clothe, arm, and equip these thousands of eager warriors than was the North. Although the South produced more than enough food, it lagged vastly behind in the capacity to produce all the varied materiel of war its armies required. At the outset of the struggle, the South had just one-ninth of the industrial capacity of the North. Eventually, the Confederate Ordnance Bureau (directed by a little-known genius, Josiah Gorgas) would succeed in arming Southern forces effectively, but the Rebel soldier from beginning to end would be ill-clothed, ill-shod, and ill-equipped, and finally, from the failure of the South’s transportation system, ill-fed. Still, by the end of April, 60,000 men were, if not exactly under arms, at least enrolled in the Confederate States Army.

Although inefficiency, incompetence and confusion reigned in both camps, North and South were swiftly raising the hosts of war. The kind of armies they raised says much about the political culture they shared. From first to last, the private soldier, North and South, never forgot that he was, like his forefathers, a citizen-soldier, and always a citizen first. It was an attitude that made turning him into a disciplined soldier a patient and demanding business. An Indiana trooper spoke for his comrades in all the Federal armies,

We had enlisted to put down the rebellion and had no patience with the red-tape tom-foolery of the regular service. Furthermore, our boys recognized no superiority except in the line of legitimate duty. Shoulder straps waived, a private was ready at the drop of a hat to thrash his commander; a feat that occurred more than once.

His Rebel counterpart was, if anything, more anti-authoritarian. A Georgia private complained bitterly,

We have tite Rools over us, the order was Red out in dres parade the other day that we all have to pull off our hats when we go to the coln or genrel… I would rather see him in hell before I will pull off my hat to any man.

Compounding this independence of mind was the fact that, early in the war at least, units elected their own officers, both at the company and regimental level. Given the inexperience of both electors and elected, the practice led inevitably to a good deal of dangerous incompetence. The testimony of a Pennsylvania soldier characterizing his regiment’s commander might be repeated a thousand times:

Col. Roberts has showed himself to be ignorant of the simplest company movements. There is a total lack of system about our regiment…. Nothing is attended to at the proper time, nobody looks ahead to the morrow…. We can justly be called a mob & one not fit to face the enemy.

So the hosts gathered that spring of 1861 from every class and calling, bearing colorful names and wearing improbable uniforms. New York Zouaves marched into Washington in baggy red breeches and purple tunics topped with a red fez. Georgia Raccoon Roughs marched into Atlanta utterly “undisciplined and undrilled… no two kept the same step; no two wore the same colored coat or trousers. The only pretense at uniformity was the rough fur caps… with long bushy streaked raccoon tails hanging behind them.” Youthful and eager they came, the Lone Star Rifles, South Florida Bull Dogs, New York Highlanders, Dixie Invincibles, Susquehanna Blues, Jasper Rifles, Cherokee Lincoln Killers, Rough and Ready Grays. Ethnic regiments came forward, primarily but not exclusively into Federal armies: the St. Patrick Brigade, Garribaldi Guards, German Rifles. Into the camps they came, clerks and college professors, Bowery toughs and ploughboys, mechanics and merchants. There they would learn how to lay out a company street properly, perform the manual of arms, and drill by company and by regiment. By daylight the private was learning “to load by nines” while his captain studied Hardee’s Tactics by candlelight to prepare for the next day’s drill. For the eastern armies of North and South, the First Battle of Bull Run was just two months away. When it came on that sultry July day, they would not quite be armed mobs, as the Prussian Von Moltke is supposed to have called them. But neither would they quite be armies.

The General-in-Chief of the gathering Federal armies was Winfield Scott. He had been a bold and brilliant commander in the Mexican War, capturing Mexico City in a campaign that the Duke of Wellington thought the greatest in modern times. But by 1861 Scott was ancient and ailing, too ponderous even to mount a horse anymore. Although “Old Fuss and Feathers,” as he was called for his pompous manner, was well past his prime as a field commander, he saw some things more clearly than most in the first spring of the war. First, he was sure that the 90-day regiments were of only marginal value and that the three-year men were months of training away from being an effective fighting force. Second, he saw the real magnitude of the task of suppressing the rebellion. While the popular press (both North and South) wrote blithely about swift and glorious victory, Scott knew that subduing the South would require vast armies and navies and a long and terrible struggle. In fact, the conqueror of Mexico City had little appetite for a war of conquest against the South. Instead, he proposed a plan to “envelop” the South by taking control of the Mississippi River and blockading her coasts. Thus isolated, he argued, the South could be brought “to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan.”

Scott’s plan, derisively called the “Anaconda Plan” by the Northern press, was on the face of it a good one. Its key objectives–control of the Mississippi and an effective blockade–would eventually become two central elements of the North’s emerging strategy. But in a democracy at war purely military considerations are never purely military. Scott argued for thorough and thoughtful preparation, and urged Lincoln to resist “the impatience of our patriotic and loyal Union friends” who demanded “instant and vigorous action regardless… of the consequences.” But the clamor of Northern public opinion and a fervid press became a call that neither Scott nor Lincoln could resist. What made the call irresistible was that it came from the people themselves in a sudden outpouring of pent-up emotion. Cities, towns, and villages turned out for “war meetings.” In New York City’s Union Square 100,000 gathered around the statue of Washington and shouted for an immediate and crushing invasion of the South. At Oberlin College, a student remembered, “War! and volunteers are the only topic of conversation or thought.” Young men turned out to enlist in numbers that overwhelmed the recruiting offices and the capacity of the states to organize them. Walt Whitman, the great poet of the people, understood that war fever was transforming the North. “An armed race is advancing,” he wrote, “welcome for battle.” In parades and rallies, in church services and schools, the theme was universal; the time had come to trust in the God of battles.

As it happened, the precise time-table for battle was actually determined in part by the press. With Virginia’s secession the Confederate government voted to make Richmond its capital and scheduled its first Congressional session to meet there on July 20, 1861. Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune announced this news with the following headline:

Forward to Richmond! Forward to Richmond!

Rebel Congress Must Not be

Allowed to Meet There on the

20th of July

BY THAT DATE THE PLACE MUST BE HELD

BY THE NATIONAL ARMY

When newspapers all over the North began echoing “On to Richmond,” the pressure on Lincoln and his war cabinet to take the offensive in Virginia mounted steadily. The government failed to act, some argued, because Lincoln was wholly unequal to the crisis. Scott himself, others hinted darkly, was after all a native Virginian and perhaps a traitor to his own government. From the people and the press came a daily cry for aggressive action. In the end, Lincoln turned to General Irvin McDowell and told him to see what he might accomplish against the Confederate Army gathered around Manassas Junction.