Introduction: Valmy

From this place and from this day forth commences

a new era in the world’s history….

–Goethe

Early on the morning of 20 September 1792, Johann Wolfgang Goethe and the soldiers of the allied armies of Austria and Prussia awoke amid the forested hills of northeastern France and prepared for battle. A few miles to the south, hidden by a dense fog, the army of the newly-formed French Republic stood ready to oppose them, yet Goethe and his comrades were full of confidence. Thus far the only serious resistance they had encountered in their invasion of France had been due to bad weather, as heavy rains slowed their supply trains to a crawl and turned their camps into miserable quagmires of mud.

The French, meanwhile, had repeatedly fallen back before a series of deft turning movements orchestrated by the Allied commander, the Duke of Brunswick, nephew of the legendary Frederick the Great and widely recognized as the most accomplished soldier in Europe. Shrewd, painstaking and deliberate, the Duke waged war with the careful calculation of a master strategist and his record stood proof of the efficacy of his methods. Perhaps his greatest feat of arms had been achieved during an all-but-bloodless campaign in Holland in 1789 in which he so thoroughly outmaneuvered his foe as to win a war without bringing on a major engagement. Indeed, Brunswick’s reputation was such that early in 1792 the revolutionary regime in Paris had tried to recruit him for overall command of French forces, an offer that could scarcely have wounded his pride. Nor was he entirely unsympathetic with the struggles of the French people. The soldier in him held out little hope for the new regime, however, and instead, he opted to lead the monarchist forces of Austria and Prussia in the cause of restoring Bourbon rule in France.

Entering French territory on 23 August, Brunswick pursued the military objectives of the campaign with his usual thoroughness. Investing the border fortress at Longwy, he secured his line of supply and proceeded westward, seizing Verdun during the first week of September and consolidating his gains in preparation for an advance to the Marne. Then the rains came, washing out roads and threatening the invading army’s ability to pursue its campaign of maneuver, to which Brunswick responded with a prudent change of plans. Rather than continue west, he proposed to move north against the fortified town of Sedan, where he thought to secure the line of the Meuse River and go into winter quarters. At this point, however, he was overruled by King Frederich William II of Prussia, who had accompanied the invading army and now took it upon himself to preempt Brunswick’s careful deliberations. Eager to score an early victory over the upstart French regime, the king insisted on cutting off the enemy’s retreat with an immediate advance upon Chalons, convinced that the combined might of the armies of Austria and Prussia would readily defeat the untried republican forces in their path.

In fairness to the king, such confidence was not unwarranted. Since the beginning of the Revolution three years earlier, the French army had suffered the loss of thousands of royalist officers, and as a result, the army’s organization and leadership were very much in transition. Among the more recent departures was no less a personage than the army’s erstwhile commander, the Marquis de Lafayette, who, despite his stature as a hero of the American Revolution, had become a target of Jacobin agitation in Paris and within the army itself. Unable to overcome his aristocratic origins, Lafayette found himself on difficult political terrain, and when a portion of the National Guard refused to respond to his efforts to restore order in the capital, he abandoned his post to join the growing number of French emigrés.

Named to replace him was Charles Dumouriez, a military careerist who assumed command of French forces even as the Austro-Prussian army was advancing upon French territory. To make matters worse, while reviewing his troops in Sedan, the new commander was greeted by jeers from soldiers still loyal to Lafayette. Dumouriez responded by drawing his sword on one of his hecklers and offering to fight a duel on the spot. The offer was declined, and Dumouriez managed to win a measure of respect in the exchange, yet his would be no easy task. “The army is in a most deplorable state,” he reported to the government in Paris, citing a general lack of discipline as well as a shortage of clothing, boots, and guns. Having originally planned to draw the enemy away from Paris by invading the Netherlands, Dumouriez quickly abandoned the scheme upon learning of the enemy’s occupation of Verdun. At this point, with Austro-Prussian forces poised to advance upon the capital, he rushed his troops south to defend a key defile through the Argonne Forest, a site whose strategic significance he compared to Thermopylae, the ancient battlefield where 300 Spartans made a desperate and ultimately unsuccessful stand against invading Persians in the fifth century BC. The analogy alone suggests something of his frame of mind.

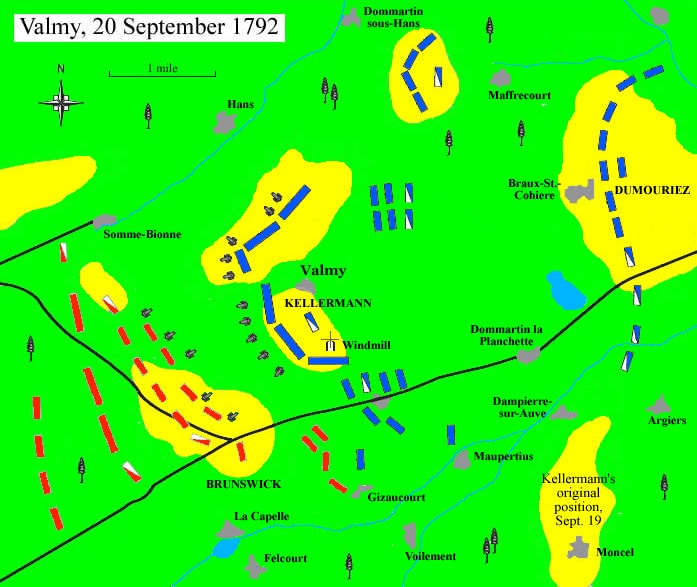

Initial contact between the opposing armies took place some 25 miles southwest of Sedan, where an Austrian detachment captured the village of Crois-aux-Bois, outflanking the French position at nearby Grandpré and compelling Dumouriez to withdraw farther south. At this point, thinking to have scored a signal victory, Brunswick called a halt and sent an emissary, one Colonel Massenbach, to French headquarters in hopes of opening negotiations. Dumouriez responded to the overture by turning Massenbach away without an audience, yet the French commander would soon have cause for second thoughts on the subject, for in the process of falling back upon Sainte Menehoud one of his corps was cut off and set upon by a force of Prussian cavalry. Though the isolated French troops managed to fend off an initial attack, a second assault sent them racing headlong in the direction of Chalons, sweeping away a large body of reinforcements in their flight and giving rise to rumors of the collapse of the entire army. With French fortunes going from bad to worse, Dumouriez’ main force–now drawn up in the vicinity of Valmy–quickly contracted the contagious fear, and had the Austro-Prussians followed up their success, they might have stampeded the French all the way to the Marne. True to form, however, Brunswick continued his cautious advance, allowing the French commander time to consolidate his position and restore a measure of confidence in his shaken troops. In this, Dumouriez would be aided by the timely arrival of French reinforcements under General Kellermann, who reached Valmy on the evening of the 19th.

Meanwhile, surprised to learn that the French were still in the vicinity of Valmy, Brunswick advanced south from Grandpré with plans to force another withdrawal. Once again, however, King Frederick William pulled rank, ordering the allied forces to proceed directly to the Chalons Road west of Sainte Menehoud in an effort to cut off an anticipated French retreat. Thus the invasion force pressed forward, going into bivouac some five miles northwest of Valmy, Brunswick’s careful campaign of maneuver having gone by the boards.

Indeed, the next morning found the Allied commander in an unfamiliar position. Now deep within French territory and effectively blinded by a pervasive fog, he was about to present his enemy with little choice but to stand and fight. Lacking precise information about the enemy’s whereabouts, he resumed his advance, and the troops had not gone far before a muffled thunder of artillery erupted on their left. Brunswick now ordered his units into battle lines, and as more cannon sounded in his front, Allied guns were rushed forward to return fire. Eventually driving the enemy back, the Austro-Prussians found themselves on high ground immediately north of the Chalons Road, having successfully interposed themselves between the enemy and his capital.

Worse still for the French, a last-minute maneuver threatened to isolate a large division of their army. Having originally taken up position on Dumouriez’s left, General Kellermann, seeking better ground, ordered his troops to advance to a hill immediately south of Valmy, placing them well in front of Dumouriez’ main line. Here his formations ran afoul of each other in the fog, becoming badly entangled in the vicinity of a large windmill. With the enemy less than a mile away, Kellermann struggled to sort out the traffic jam as urgent voices and clanking gear echoed eerily through the fog. To the Austro-Prussians on the hill opposite, the resulting cacophony gave hope of another French withdrawal, a hope reinforced by word that Allied units were moving into position on the French flank. Peering intently into the fog, Goethe and his companions waited eagerly for signs of the enemy’s departure.

About noon, however, a rising wind cleared away the fog to reveal solid lines of French infantry along the face of the hill. Despite considerable confusion, Kellermann’s troops had come into position, and in addition, Dumouriez had rushed reinforcements forward south of the Chalons Road, where the steady crackle of small-arms fire told of solid resistance to the Allied flanking force. Moments later, in the vicinity of the windmill, Kellermann himself could be seen waving his hat upon the tip of his sword as resounding cheers were heard along the length of the French ranks: “Vive la nation! Vive la France! Vive notre general!”

Next, the heavy guns of both armies opened up, and what followed was a cannonade of epic proportions. Over the course of the next four hours, tens of thousands of shells were fired, creating a din beyond the experience of even the oldest veterans. Amid this withering barrage, the soldiers on both sides remained in formation, providing easy targets for the artillery crews. (Things might have been worse, as the hurtling balls of iron tended to lodge in the rain-saturated ground, causing the earth to shake violently yet resulting in relatively few casualties.) About 2 p.m., a huge explosion was heard in the French rear as a number of ammunition wagons were hit, causing considerable slaughter. A lull in the firing followed as the Allies waited expectantly, hoping to see a wave of panic carry off the enemy formations. When the smoke cleared, however, the French were once again holding fast to their positions.

What happened next would cast a long and fateful shadow on Royalist ambitions throughout the continent. Thus far the Austro-Prussians had clearly been the aggressors, invading enemy territory and threatening the conquest of the French capital. Yet when the time came for Brunswick to make good this threat in a final test of arms, he demurred, declining to order an attack and instead shifting his position slightly to the south. For the next several days the two armies remained opposite each other while the Allied commander once again pursued negotiations, seeking to convince the French of a defeat they had not suffered. Then, on the night of 30 September, Brunswick abandoned the invasion altogether, slipping away to the east and recrossing the Meuse.

Thus, the engagement at Valmy became a French victory by default, a fizzled contest to crown a fizzled campaign. And yet, the abortive battle would have far-reaching implications, for in prevailing against the vaunted might of the Austro-Prussian army, the French would experience the first stirrings of an intense national pride that would eventually carry them to victory after victory and ultimately change the nature of warfare. Heretofore waged almost exclusively by hirelings on behalf of ruling elites, wars would increasingly be fought by vast armies of conscripts on behalf of nation-states. Thus, the style of warfare in which commanders such as Brunswick sought to outmaneuver their opponents rather than actually defeat them by force of arms would become a thing of the past. Inspired by the same powerful forces that had given rise to the French Revolution, the French national army would soon set a new standard for offensive warfare in which the spirit of the attack–or élan–would dominate.

At least two witnesses to the encounter at Valmy sensed in its aftermath an immediate shift in the European balance of power. One, the same Colonel Massenbach who had served as Brunswick’s emissary, would write of the French: “You will see how those little cocks will raise themselves on their spurs… We have lost more than a battle. The 20th September has changed the course of history.” The response of poet and dramatist Wolfgang Goethe struck a similar, if more sanguine, note: “From this place and from this day forth commences a new era in the world’s history,” he told his companions, “and you can all say that you were present at its birth.” He too recognized a changing of the guard in the wildly cheering French soldiers who had opposed the Allied monarchies–and all the feudal arrangements of the past–with such enthusiastic audacity. Having already embraced many of the ideas and attitudes associated with the French Revolution, Goethe would soon come to admire a figure who would not only master the new style of warfare but ultimately symbolize all the energy and idealism of the new age. Then a newly-commissioned lieutenant on leave in Paris, Napoleon Bonaparte was about to embark upon an unprecedented rise to power.